The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), 2005, was notified on 7 September 2005.

The mandate of the Act is to provide 100 days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year to every rural household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.

MGNREGA has been a core programme of Pragati Abhiyan since its inception. We are doing awareness generation and mediation for work allocation to tribal people, including single women, through MGNREGA. Along with building capacities of Village Volunteers for extension of MGNREGA scheme to the tribal villages and to ensure access to all facilities and entitlements MGNREGA labourers get, especially for women such as creches, drinking water and so on.

Regular implementation of MGNREGA during non-agricultural seasons has helped curb distress migration in several Adivasi villages. As expressed by women, this has contributed to the well-being of women and children and continuity in children’s education. It has also contributed to water conservation and improved irrigation support by creating water bodies, making many villages water positive.

With years it has not only gained ground but has also become a core strength of the organisation. Due to this enriched and experiential knowledge base, Pragati Abhoyan is seen as a resource organisation in all aspects of MGNREGA, from awareness to training and hand-holding to research and advocacy.

Unique Training Modules

Pragati Abhiyan has developed unique training modules based on its field experience and collaboration with the government to strengthen the implementation of MGNREGA.

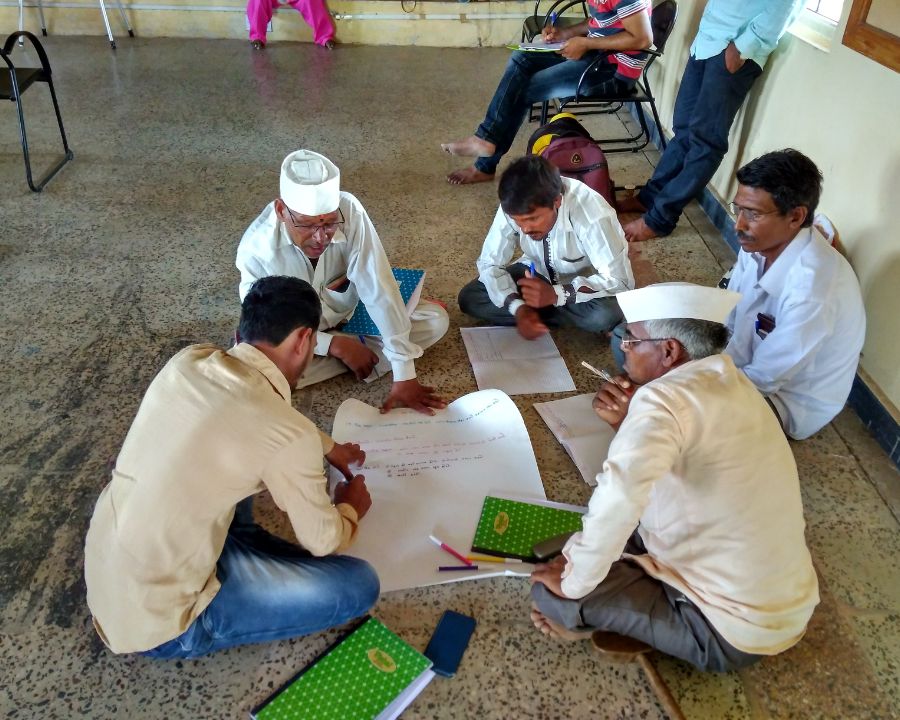

Gram Rojgar Sevak Training

Focused on empowering Gram Rojgar Sevaks who play a crucial role as intermediaries between workers and implementing agencies with the knowledge, skills, and motivation to support effective and transparent delivery of MGNREGA.

Sarpanch and elected representatives Training

Designed to build awareness among village Sarpanchs and elected representatives about entitlements, procedures, and rules under MGNREGA, and to support their leadership in planning village-level employment works.

Community-Level Trainings

Conducted with village youth and volunteers to mobilise demand for work and strengthen grassroots implementation of MGNREGA in tribal areas.

Training for Government Workers

Organised for officials from departments such as Agriculture, Revenue, and Rural Development to enhance their understanding of MGNREGA and improve coordination for effective execution.

Training for Civil Society Organisations

The organisation offers training and handholding support to NGOs across Maharashtra and beyond, enabling them to initiate or strengthen MGNREGA-related interventions. During the COVID-19 lockdown, a series of online sessions were conducted for field workers and volunteers of partner organisations.

Our Model: A Three-Year Cycle for Building Local MGNREGA Systems

From our experience across multiple districts in Maharashtra, a minimum of three years is the essential gestation period required to set the annual MGNREGA work cycle in motion in any village. It takes that long for the community to begin understanding their rights under the Act, for demand-based planning to become a norm, and for local administrative systems to respond reliably.

In 2019, with support from a donor agency, we had the opportunity to put to test this model and to scale and systematise what we had been practicing for years. This allowed us to consolidate our field learnings into a structured three-year model and expand MGNREGA-related work across 17 blocks in 13 districts of Maharashtra. Even in villages where no MGNREGA activity had taken place for years, we found that it was possible to initiate and strengthen a regular work cycle within two to three years—provided the right foundation was laid through local engagement, capacity-building, and consistent follow-up.

For those who are discouraged by the delays, refusals, or frustrations of dealing with the system- here is the model that has worked for us. It is grounded in field experience, sustained engagement, and a belief that even the most unresponsive system can shift when communities are equipped, confident, and persistent.

The Role of Local Resource Persons

Our approach begins with identifying a Cluster Resource Person (CRP)—a local resident familiar with the language, geography, and natural resources of the area, and rooted in their community. Once identified, the CRP undergoes capacity-building sessions that combine classroom training, peer learning, skill development, and field mentoring. CRPs are trained not only on the legal and procedural aspects of MGNREGA but also on communication, negotiation, and facilitation.

In the field, CRPs engage directly with workers, Gram Rojgar Sevaks (GRS), panchayat members, and frontline government functionaries. As their confidence grows, they begin to liaise with block and district-level authorities as well. Regular fortnightly review meetings create a space for CRPs to reflect on experiences, share challenges, and refine their strategies.

Generating Demand: The First Step

One of the most critical phases is post-Kharif (November–January), when harvesting is over, and farmers often migrate for construction, sugarcane cutting, or brick kiln work. This is when CRPs initiate conversations with men and women villagers about their needs and aspirations, and introduce MGNREGA as a means to access local employment and village development.

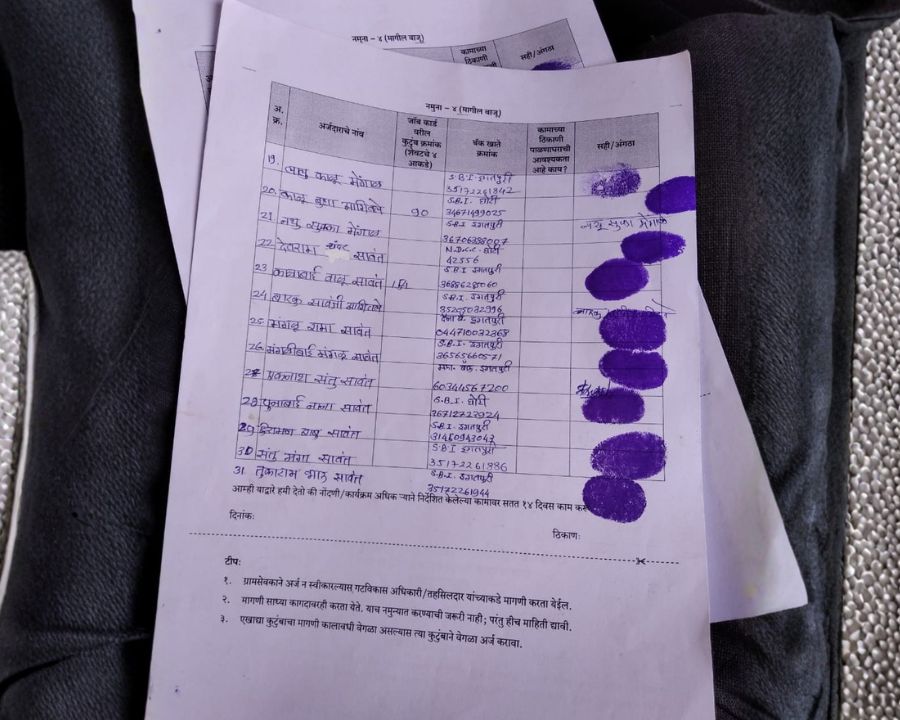

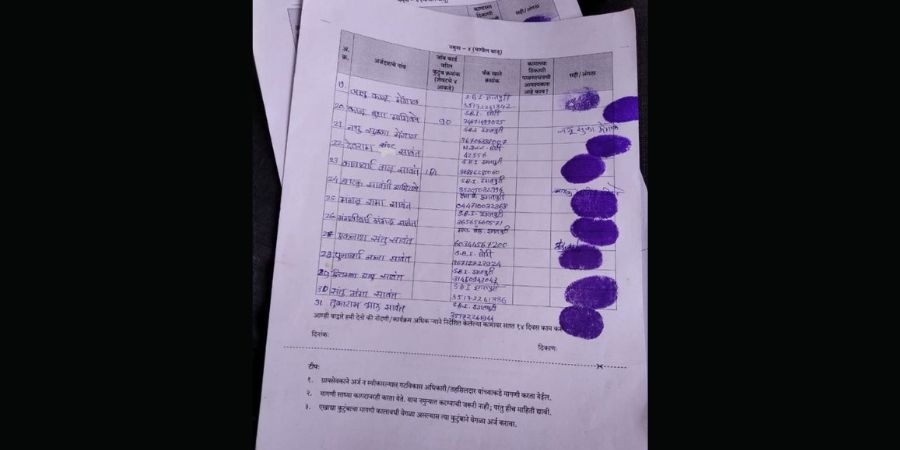

These dialogues focus on identifying individual and community-level needs and prioritise women’s needs, such as land levelling, bunding, farm ponds, animal shelters, vermicompost pits, internal roads, water storage structures, afforestation, and more. Demand is central to how MGNREGA functions, and the process of preparing demand applications - with names, job card numbers, bank details - is supported by the CRP. These applications are submitted to the GRS or GP, and if they are not accepted, escalated to the Block Development Officer (BDO) with formal receipts.

Reaching this stage is not easy. CRPs often encounter multiple refusals, misinformation, and delays. But it is crucial to cross this threshold, because only then does the administration begin to take the community’s demand seriously.

When Work Begins: Monitoring and Follow-through

According to the Act, work must begin within 15 days of application. While this rarely happens in villages where MGNREGA had long been dormant, persistent follow-up often results in some work being sanctioned. However, the type of work, number of workers engaged, and duration of work are often limited - designed more to discourage than to support. At this stage, CRPs must remain vigilant and keep demanding appropriate works that match the number of applications and ensuring that entitlements are met.

As the demand becomes consistent, Panchayat and PS officials begin to realise that workers are serious and persistent. This often leads to a moment of reckoning that there is no approved “shelf of works” available. The “shelf” refers to technically approved works that are ready for implementation. Without this, even genuine demands cannot be acted upon.

Worksite Monitoring and Worker Entitlements

Once work begins, CRPs and workers monitor daily processes closely. Attendance, whether on physical muster rolls or e-muster tabs, must be recorded twice daily, with photos uploaded in digital formats. CRPs along with labourers ensure that basic worksite facilities, such as drinking water, resting sheds, first aid kits, information boards, and sample pits, and a creche if applicable, are available and functional.

Equally important is the process of weekly measurement by technical staff from the Panchayat Samiti. Since wages are based on measured output, CRPs are trained in measurement techniques to support workers in seeking re-measurement if errors or delays occur. Wages for men and women are equal and must be paid within 15 days of work completion. Once the pay order is generated and fund transfer initiated, wages are deposited directly into workers' bank accounts. This 15-day cycle - demand to work to payment - forms the backbone of the MGNREGA implementation process.

Planning Ahead: Creating the Shelf of Works

While implementing work is crucial, planning for future work is equally important. During the monsoon season, when farmers are occupied in their fields, CRPs walk with them across their lands, forests, water bodies, and public spaces - identifying needs and helping envision developmental works. These may include deepening ponds, rejuvenating old water structures, afforestation near community buildings, or constructing roads that connect hamlets and farm plots. At the same time, meetings with the communities to identify individual benefit schemes and prepare applications for the same.

These needs are formalised into proposals, which are presented during 15th August and 2nd October Gram Sabha meetings. Once resolutions are passed and endorsed, they are submitted to the Panchayat Samiti for technical scrutiny and approval. When approved by the BDO, these works become part of the official MGNREGA shelf, ready to be sanctioned as and when demands arise. They remain on Shelf as it is not time bound by financial year closure.

From First Cycle to Long-Term Systems

The first cycle of MGNREGA work in a village - mobilised and facilitated by the CRPs - is always a mixed bag of successes and challenges. Nothing moves smoothly, and not all efforts yield immediate results. Yet, every round brings learning, collective confidence, and administrative recognition. Within two years of consistent effort, a cycle sets in - villagers know how to demand, officials expect the demand, the shelf is prepared in advance, and work begins in time. A local system begins to take shape.

This, we believe, is the essence of making MGNREGA work - not as a scheme to be “delivered” to people, but as a right to be claimed, planned, and sustained through local participation, persistence, and practice.

We have published a book of stories of experiences of a few of the CRPs, which can be found here.

Impact Highlights

100+

100+

Reduction in distress migration by 20% in target Adivasi villages.

Campaigns & Resources

Kaam Mango Abhiyan (2013)

In 2013, after experiencing that the demand for work is low, even eight years after the MGNREGA came into being, civil society organisations across the country launched ‘Kaam Mango Abhiyan’ to build awareness among people and encourage the administration to capture the demand. Pragati Abhiyan co-ordinated and led the campaign process in Maharashtra with active involvement of over 35 organisations in the state. The campaign reached out to people, explained to them the significance of the scheme and helped them to raise the demand for work.

Swabhimaan Rojgar Yojana

With funding support from like-minded friends, Pragati Abhiyan implemented a novel idea – Swabhiman Rojgar Yojana - to create water storage structures to mitigate the impact of drought. The idea was to implement NREGA as it is meant to be with one important difference – it will be privately funded. This initiative, implemented for three years in four villages from Amlon block, was coordinated by a friend and supporter of the organisation.